On the Right is an academic blog that provides critical analysis and insight into contemporary right-wing politics and ideologies around the globe.

Dr. Meredith L. Pruden is an Assistant Professor in the School of Communication and Media at Kennesaw State University, as well as a Fellow with Institute for Research on Male Supremacism and an affiliate with the Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life (CITAP) at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Meredith earned her PhD in Communication and certificate in Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies from Georgia State University...read more.

Karen Lee Ashcraft, Wronged and Dangerous: Viral Masculinity and the Populist Pandemic

May 1, 2023

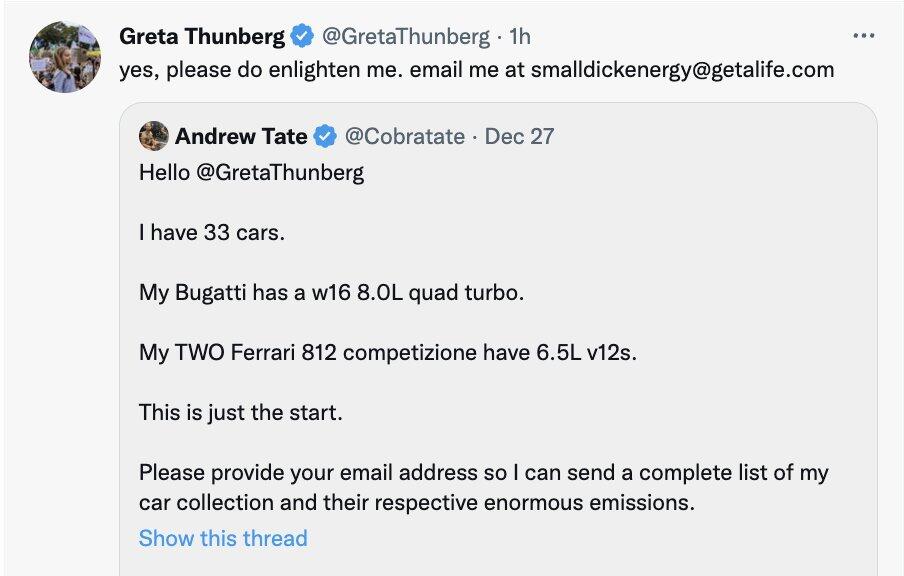

In December 2022, as I was reading Karen Lee Ashcraft’s Wronged and Dangerous: Viral Masculinity and the Populist Pandemic in preparation for the review I now write, a brief exchange took place on Twitter between a young climate activist and a nearly middle-aged former professional kickboxer:

Combined, these two tweets—shared between an upper-middle-class white Swedish female teenager (at the time of tweeting) on the autism spectrum and a thirty-six-year-old, cis-hetero, mixed-race, US-British expat living in Romania (and avowed misogynist) with a purported net worth in the tens of millions—garnered some 540 million views, 240,000 likes, 703,000 retweets, and tens of thousands of comments. They are a snapshot into the sort of viral masculinity about which Ashcraft writes in Wronged and Dangerous and a prescient reminder of Ashcraft’s warning that blaming and shaming aggrieved masculinity simply does not work to change the hearts and minds of its adherents. But, more than that, they exemplify Ashcraft’s call to employ a public health frame to the “pandemic of feeling” that is “New Populism’s” particular brand of aggrieved masculinity, which is, in essence, an identity politics hiding in plain sight.

Ashcraft provides four reasons for her public health framing, which I will unpack more fully later in this review but want to relate directly here to the exchange between Thunberg and Tate. First up—harm to others. Despite allegations of interpersonal violence against women, including physical assault and rape, as well as human trafficking, Tate is a hero of the manosphere (a darling, if you will), and his December 2022 arrest in Romania on suspicion of organized crime and human trafficking seems to have also made him something of a martyr, with protests of angry young men erupting in Greece shortly thereafter.[1] While Tate has yet to be indicted, he has spent several months in jail and was moved to house arrest in late March pending a court appearance in this case. In other words, he is networked misogyny personified. A second point—generalized harm. According to Ashcraft, generalized harm is about collateral damage. Chief among them, in addition to the mishandling of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, is the global climate crisis. She points to the “link between environmental damage and masculinity” (168), wherein green initiatives are feminized in the human-versus-nature binary, and the backlash—exemplified by such practices as “rolling coal” and driving oversized cars with high emissions (like those Tate tweeted about)—equates to “proof” of dominant masculinity.[2] The third point is what Thunberg terms “small dick energy” in her tweet and Ashcraft calls “death by pufferfish” in the book. In both cases, aggrieved masculinity is a performative blowing up that is fueled by the perceived (that is, felt) threat against dominant manhood. Ironically, according to Ashcraft, a pufferfish response based in aggrieved masculinity and white racial resentment is “a major cause of physical disease and death” for men that threatens white men’s health (170). Finally, Ashcraft refers to “pufferfish at scale” as the fourth way in which New Populism’s aggrieved masculinity demands a public health approach. Pufferfish at scale refers to the evolution of backlash politics, resulting in antigovernment sentiment and the removal of government-sanctioned health and safety protections. These removals, of course, lead to negative health outcomes for everyone—including the most privileged men (cis white men) who stoked the ire in the first place. An example of pufferfish at scale, related specifically to Tate, is the surge in support for Tate following his arrest, which included discussions around men’s rights, mental health, and free speech, both in the court of international public opinion and in some Western courts of law.[3] Tate’s arrest has become one more example of so-called cultural Marxism running roughshod in nations the world over.

As I hope this brief example demonstrates, Ashcraft’s Wronged and Dangerous is a timely, relevant, and much-needed corrective to academic accounts of right-wing populist animus that downplay, ignore, or, occasionally, downright erase gender as an analytic approach. However, to be clear, there are scholars working across a variety of disciplines who already aptly deploy Ashcraft’s recommended gender-first framework to studies of the far right, conservative populism, white nationalism, and (of course) the manosphere. In fact, I count myself among them. The lack of attention to issues of intersectionality in academic accounts of populism and, specifically, the far right is one of the main reasons I branched out from work on the manosphere some five years ago. But, as Ashcraft makes abundantly clear, these folks remain relatively few and far between. Instead, Ashcraft argues, many scholars take a class-first approach to this issue that amounts to a “collective denial” of binary gender norms and relevant gender-based resentments as the root cause of the phenomenon. At the end of the day, Wronged and Dangerous is as much about viral aggrieved masculinity’s connection to right-wing populism as it is about a sociophysical analytic approach. This sociophysical analytic approach, which understands reality as “social and physical at once” (15), addresses gender from an intersectional perspective and is, thus, better equipped to confront right-wing populism laterally—what Ashcraft calls empathy from the side or the “communicability of feeling” (3). In other words, lateral empathy recognizes how viral masculinity (as feeling) spreads but stops short of justifying associated complaints. This contrasts with other common responses to populist grievances—oppositional blaming and shaming or compassionate empathy from the front—both of which legitimize such complaints by meeting them “on [their] own terms” (4). Researchers rooted in more critical fields will likely find themselves nodding in agreement with the author’s call to break down the well-worn binaries allowing gender to establish social hierarchies and adhere to marked bodies, while those unversed in intersectionality will find this work accessible and, I expect, also an incentive to more deeply consider “gender as a force in everyday encounter” (53).

Wronged and Dangerous is organized into four parts, each containing five relatively brief chapters. Part 1, titled “Gender as an Acquired Taste,” lays the foundation for what follows and provides a high-level overview of some of the central tenets of the book—rooted primarily in feminist, critical race, and sexuality studies (though Ashcraft is an organizational communication scholar). The author introduces the necessity for a co-constitutive sociophysical approach (in which “the social and physical worlds are already one . . . reality is social and physical at once”) to viral masculinity by problematizing normalized gendered thinking that sees reality as material/hard/masculine or socially constructed/soft/feminine (15). In addition to this theoretical contribution, the author provides a more applied contribution by naming a series of “bad habits” folks tend to have related to gender, and ways to fix them. For instance, one such bad habit is “gender = women” (28), which is the notion that gender is of foremost concern when talking about women, and subsequently, a universal group of women is constructed. In contrast, men are primarily seen as individuals first and not commonly viewed as a universal, gendered group. Ashcraft’s solution to this bad habit is to remind ourselves to see gender on everyone—especially men, since this is where it is commonly erased—and to think frequently about how the world is gendered (28). To demonstrate binary gendered thinking, Ashcraft offers two case studies, analyzed through the lens of common media and scholarly responses. The first reviews the handling of national COVID-19 responses by “populist strong men” versus women leaders (21). In Ashcraft’s words, “In short, gender was a side story when it came to men and populism but the lead story when the leaders in question identified as women” (21). For instance, populist strong men who did a poor job of handling their nation’s COVID-19 responses were still seen in terms of individual shortcomings rather than men’s failings. On the other hand, more effective COVID-19 responses by women leaders were often attributed not to individual attributes but to the mere fact they were women. The second, related, case examines “mask-ulinity” and further unpacks hierarchies of power already noted in the first case. Here, Ashcraft notes some promising changes—insofar as “mask-ulinity” is often recognized more intersectionally as a conservative white male phenomenon—while also tracing a brief history of mask wearing and how gendered performances around masking are communicable feelings that come upon us, often seemingly out of nowhere. Taken together, this section of the book is an excellent primer on the widespread damage such binaries produce on a global scale, as well as a good reminder for those who are already knowledgeable.

Part 2 of Wronged and Dangerous, titled “The Feel of New Populisms,” shifts gears to a review of populism and its commonly cited attributes, its evolution to New Populism, and considers why existing anti-populist approaches fail to achieve their stated goals and what viral masculinity has to do with it. Drawing on work by political scientist Cas Mudde and others, Ashcraft describes populism as a “thin-centered” ideology, meaning it is ideational, deliberately ambiguous, and highly malleable as a result.[4] Moreover, there are several traits commonly associated with populism, which Ashcraft provides. These attributes include narratives of the people against the establishment (sometimes referenced in the book as the “deep state”), a general sense of us-versus-them antagonism (that is sometimes three-dimensional and includes Othering), a veneer of flat organization and direct communication from charismatic leaders, and a tendency to employ an aggressive rhetorical style. Turning to New Populism, which Ashcraft notes is more accurately described as New Populisms, the author makes the case that something has changed in recent decades. Specifically, among other things, she notes that New Populism needs democracy to thrive and alters democratic practices in the process (notably by governing as antigovernment). It also takes advantage of new media environments to more widely and efficiently spread its agenda, which is more about feeling than ideology.

What is that feeling? The sense of aggrieved masculine entitlement, according to Ashcraft, is paramount, and it is why standard antipopulist approaches (e.g., shaming the base) not only do not work but also wind up justifying right-wing populist resentment. Instead, she suggests we view populist viral masculinity as a “downrising” of “spiraling momentum” that includes not only the base but also elites, the left, and technologies (86). A “downrising” refers to the “dispersed agency of New Populist feeling,” and it encapsulates the ways in which humans (the left, the right, everyday citizens, elites) and technology contribute to it. This shift is intended to shed light on the ways in which actors other than the conservative base are implicated in right-wing populist sentiment. The elites on the right, for example, fund astroturf movements and stoke populist resentments in campaign speeches, media interviews, and on their social media handles. The left (while not equally culpable) can entrench such resentments when they blame and shame conservatives and when they act as “dismissive elites” (91). Finally, Big Tech platforms that monetize outrage, mis- and disinformation, and conspiracies because they net more eyeballs and longer times on platform are deeply implicated in the virality of populist masculinity.

In part 3, “Probable Cause,” Ashcraft tackles class-forward approaches to New Populism, the “collective denial” of gender as its cause, and how aggrieved entitlement moves as New Populist anger (120). She also provides an example of an intersectional, gender-first analysis using a case study of two films (more on this later). Class-forward approaches to New Populism break down, according to Ashcraft, because its sentiment is not only, or even mainly, about economic inequality. Nor, she says, is it primarily about cultural marginalization, or racial and religious resentment. It begins with gender. Full stop. As Ashcraft writes, “New Populism . . . is precisely what populism is not supposed to be—a project of identity politics. It is a gender-based movement that vents and soothes aggrieved masculinity by (re)claiming its generic status as The People” (106). For this reason, she argues we must think about class as intersectional because it so often stands in as a substitute for identity and culture.

Here, Ashcraft heads off several commonly cited reasons why New Populism cannot be about gender. These denials include such defenses as that women also participate in these movements, patriarchy is so common as to be a nonstarter for analysis, hypermasculinity is on the fringes, and other similar repudiations. However, Ashcraft unpacks these denials. Related to women’s involvement, she notes that “masculinity is available to everyone” (122) and gendered norms around compulsory heterosexuality incentivize women—especially white women—to participate in New Populism even if it means supporting “strongman” leaders. Related to the ubiquitous and common nature of patriarchy, she notes that “common doesn’t make it commonplace” (123). In other words, “patriarchy is no mere residue; it’s still here because we’re still doing it” (123). It is a result of our ongoing “gendering practices” (124). Moreover, related to hypermasculinity as fringe, Ashcraft briefly traces how antifeminist and masculinist groups have become the core of New Populist movements. In sum, the author does an admirable job dismantling them each in turn before exploring how New Populist anger moves. This movement happens because aggrieved masculinity “is the sensational linchpin” that “runs on a binary code that is easy to translate” (136–37).

Ashcraft rounds out this section with an intersectional, gender-first analysis of the films Fight Club and The Joker (mostly focusing on The Joker) to demonstrate how masculinity and class are co-constitutive in New Populism. This section shows how starting with gender and moving outward to other identity markers, as well as to cultural, political, and economic contexts, nets a richer evaluation. Ashcraft begins by historicizing aggrieved masculinity in the context of men’s movements dating from the 1970s before moving into how it has reared its head in outrage media, the Tea Party, and other such spaces. Against this backdrop, Ashcraft highlights not only how the content of The Joker—for instance, its protagonist is in a crisis of masculinity, a beta picked on by alphas and an unpopular comedian in a crumbling city, who ultimately exacts his catastrophic revenge—connotes the stickiness between white male grievance and class oppression, but also how the film’s creation in and of itself tells the same story. In brief, the film’s writer, producer, and director created The Joker as a response to “woke” Hollywood’s supposed cancellation of bro humor—and received eleven Oscar nods for his “trouble” that year.

Ashcraft’s analysis of The Joker points to three “unsustainable supremacies” in relation to aggrieved masculinity and New Populism (152). The first supremacy is an “expectation to come ahead of Others,” which is thwarted both by top-down injustice and by bottom-up cheating (153). The second is “identification with the universal subject,” which causes these men, when asked to “acknowledge their own partial identity,” to read this request as a form of “reverse discrimination” (153). Finally, the third supremacy is “the pursuit of self-containment” or the “foundational fantasy or potent impermeability,” as contrasted with the constant permeability of women and Others (153). Not only are these supremacies present in The Joker, according to Ashcraft, but the film also functions as one among many cultural narratives that circulate and reinforce manly grievance and the supposed crisis of masculinity.

Finally, part 4, titled “Virality and Virility,” transitions to positioning viral masculinity and New Populism (or perhaps, in Ashcraft’s terms, viral masculinity as New Populism) through a public health frame. Crucial first steps to taking a public health approach to the phenomenon, she says, are moving from toxic to viral masculinity and employing lateral empathy to better recognize that New Populism is about “the feeling of manhood under siege” because that feeling is real even if it is not true (159). Ashcraft unpacks at some length why understanding New Populist masculinity is better accomplished through a viral, rather than a toxic, frame. In other words, she argues for a move from toxic masculinity as poison to viral masculinity as the communicability of feeling.

To be clear, Ashcraft is not suggesting that we empathize with the content of New Populist arguments. Rather, she is suggesting we acknowledge aggrieved masculinity as a “sociophysical contagion” and work to stop its spread (160). While I am not generally a fan of viral framings to describe nonmedical phenomena, the author does make a persuasive case for its use here through the connection to bodily sensation and detrimental health outcomes. As mentioned, Ashcraft cites four reasons for New Populism as a public health concern. First, a litany of evidence implicating this political “pandemic” in harm to others—for example, online and networked misogyny, interpersonal violence, and mass killings. Second, evidence of more generalized harm, such as failure to address the climate crisis and the handling of COVID-19 responses. Third, anger over imperiled manhood, which exacerbates health risks, such as physical disease and death, for those attuned to the bodily sensations of aggrieved masculinity, what she calls “death by pufferfish” (170). One example Ashcraft provides for death by pufferfish is white male support for Second Amendment rights, which has contributed to disproportionate suicide risk for that demographic. Fourth, “pufferfish at scale,” aka backlash governance (172).

Part 4 also digs into how feelings of “manly right, wronged” move across the manosphere (and beyond), examines the case of critical race theory (CRT) through the lens of the manosphere-as-playbook, situates New Populism (and the manosphere) as a brand, and challenges readers to adopt critical feeling practices (184). Drawing on work by Sarah Banet Weiser and others, Ashcraft attributes the “animation” of “manly right, wronged” to networked misogyny as a growing transnational movement not limited to online spaces. In this way, she asserts, the manosphere functions as a “sociotechnical hive of activity” that circulates and amps up sensation, connects it to local contexts, and focuses all that affective energy onto supposed culprits (184). Because the manosphere behaves in this way, according to Ashcraft, it doubles as a New Populist playbook for waging culture wars and, ultimately, shaping public policies. She traces the rise of anti-CRT campaigns—from a “local” newspaper op-ed with Heritage Foundation connections and a conservative think tank alum on a mission, to outrage media and a US senator’s speech, oddly similar to the original op-ed and to common manosphere narratives, at the National Conservatism conference—as one example of how the manosphere proof of concept was used to usher in a barrage of anti-CRT state and federal legislation. Ashcraft also uses this example to connect the manosphere and New Populist identity politics to neoliberal sensibilities around branding and communicative capitalism insofar as they all function through a “less conscious” sensation designed to be shared like commodities in an attention economy (206).

Ashcraft wraps the book with a “call to arms” and a call for help, asking, “What would it look like to approach the culture wars this way, as if virus mitigation were the charge?” While she admits she is unsure of the answer, she does hint that “critical feeling” from a place of lateral empathy is a good place to start (209). Critical feeling, according to Ashcraft, is a way to awaken and attend to our oft-neglected senses that are outside systems of representation. In other words, critical feeling cultivates an attention to the ways in which affect and emotion exacerbate the circulation of ideologies because feeling is what allows ideology to sneak up on us through the “sensory ‘side doors’” (212). These side doors are where Ashcraft asserts we are especially unaware or even sensorially illiterate (Westerners in particular). Therefore, she offers several questions one can ask oneself related to critical feeling but connecting “brain with body,” for example, “How did I come to feel this?” or “How did it grow so intense as to seem irrefutable?” (213). Here, Ashcraft employs what she considers to be populist concepts (lateral empathy and critical feeling) alongside her public health frame for harm reduction in the face of New Populist viral masculinity.[5]

While Wronged and Dangerous is a straightforwardly written, timely, and at times quite funny contribution to our understanding of the gendered nature of populism (providing, as well, practical advice on the same), I have a handful of quibbles, which I hope are read as a good-natured response to the author’s “call to arms.”

I have four theoretical comments, followed by several admittedly personal—yet relevant—gripes. I will begin with the former. First, Ashcraft’s sociophysical approach feels like strands of feminist sociology’s symbolic interactionist frameworks, such as “Doing Gender.”[6] While she does spend some time unpacking social constructionist and performance models, their relevance to her own approach could be examined more explicitly. Second, it seems implied that the brand of New Populism Ashcraft highlights is right leaning, but this clarification goes largely unstated. A more explicit connection to right-wing or conservative or radical-right populism would be beneficial. Third, one of the hallmarks of populism as a thin-centered ideology is that it needs to be grafted on to other thicker ideologies. Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser name tribal nationalism.[7] Ruth Wodak names neoliberalism.[8] Male supremacism is another such thicker ideology, but this is left unexplored. Fourth, in a book that urges us to unlearn binaries, I am unconvinced by Ashcraft’s suggestion that the point of New Populist hostility is the sharing of feeling and not content, with the content being merely a “bonus” (188). While this is an inversion of the hard/soft binary that historically viewed feeling as soft/feminine and content as hard/masculine, it remains a binary nonetheless. I am left wondering, why not both/and?

Onto the latter. While I have no full-throated recommendation for alternatives, I do not agree with Ashcraft’s assertion that the “manosphere is the best term we have for capturing how far-right communities operate as an interconnected whole, a transnational movement adhered by the glue of the gender binary,” nor that we should stop using terms like “far right” or “white nationalism” (179). For one thing, while her suggestion valuably foregrounds gender, it runs the risk of erasing other supremacisms. It is possible to take a gender-first approach and emphasize the role gender plays in these spaces without lumping everything under the manosphere. For another thing, white supremacist groups (also usually sexist) were among the first to use the internet for recruitment and mobilization—they preceded what we now call the manosphere, to which they clearly remain connected.[9] Additionally, in the discussion of populism and New Populist grievances, the “deep state” is referenced by Ashcraft more than once. This feels like a lost opportunity for interrogating how intersectional gender-first analysis also must consider other identity categories. The deep state as a concept, for example, can be traced back to antisemitic and antiglobalist conspiracy theories about the supposed Zionist Occupied Government, or ZOG. Finally, an in-text accounting of why many feminist scholars no longer cite by name the original author of the notion of aggrieved masculinity is warranted. While Angela Nagle gets a nuanced critique in the main body of Ashcraft’s text, only a vague critique of this other author is provided in the endnotes, which feels like an important oversight.

Despite these critiques, Karen Lee Ashcraft delivers a compelling account of how the bodily sensation of aggrieved masculinity as New Populist identity politics is felt by human beings, how it is shared widely, expediently, and effectively, and how it ultimately causes individual and generalized harm in the process. It is my hope that scholars across disciplines use this book to take stock of their own “bad habits” related to gender and populism and to build better ones in their place by heeding her call to take up this intersectional work in their own regionally specific contexts. As a fellow traveler on this research trajectory, I am excited to see how folks blaze their own trails using the framework Ashcraft has provided in Wronged and Dangerous.

[1] Nilofer Khan, “Andrew Tate’s Fans Chant ‘Free Top G’ in a Viral Video; It Portrays the Malevolent Atmosphere He Has Created,” Mashable, January 19, 2023, https://me.mashable.com/culture/24193/andrew-tates-fans-chant-free-top-g....

[2] The term “rolling coal” describes vehicles, usually large trucks with diesel engines, that have been modified—against environmental protection laws in the United States and elsewhere—to produce huge plumes of black smoke. “Rolling coal” has been noted by some pundits and researchers to be a form of right-wing provocation in the so-called culture wars.

[3] Tate is considered by many journalists, researchers, and fans to be a men’s rights influencer for his brand of masculinity. He has also publicly stated several times that mental health problems are not real, and he is a vocal advocate for unfettered free speech. These elements not only elevate his profile among disaffected men but are touchpoints for larger culture war debates, some of which make their way into US state or federal policy and other Western contexts as well.

[4] For additional context around populism, see Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019); Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, “Populism,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies, edited by Michael Freeden, Lyman Tower Sargent, and Marc Stears, 493–512 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[5] Ashcraft sees these concepts as being more “richly” populist than New Populism because they are “of, by, and for The People,” cannot serve “narrow interests,” and cannot be “handed off to the experts” (214).

[6] Candace West and Don H. Zimmerman. “Doing Gender,” Gender & society 1, no. 2 (1987): 125–51.

[7] See Mudde and Kaltwasser, “Populism.”

[8] Ruth Wodak, The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean (Los Angeles: Sage, 2015).

[9] The white nationalist web forum Stormfront, for example, was founded in 1990.